About the methaphysical content of the EM field

Some phylosophical gambling around physical ideas

The principle of conservation of energy is one of the central pillars in modern physics. There are many different forms of exchangeable energy. However, how much metaphysical content does each one of these different notions of energy have? Is it a must to believe in such manifestations of energy in order to describe the behaviour of the world? The usefulness of such concepts is out of question, especially when used as mathematical tools to model physical systems. But at a more fundamental level, do we need to believe in them?

There are many ways to address this question and contextualize it into more complex discussions in philosophy, such as the debate of realism-antirealism. In this blog post I would like to focus on one of these energetic entities: the electromagnetic field and the photon.

Most of the objects we see and we experience in our everyday life are described by Classical Electromagnetism (EM), the theory that describes the behaviour of electrically charged particles and electromagnetic waves (light)

Once we have the force, we can use Newton’s equation to compute the trajectory of charged particles given some initial conditions. Then, a standard problem that will rise in an electromagnetism course will be this: computing the EM field that a set of charged particles moving in space generate in order to infer the effect that these will have in the movements of any other particle.

Even more, Maxwell’s equations allow us to compute the evolution in time of \(E\) and \(B\) given some initial conditions of the field plus boundary conditions (that is, the value of both \(E\) and \(B\) on a surface that surrounds our physical system; if we are considering an open system without boundaries, we don’t need to specify this). In the latter case, there is no need to specify the state of the charged particles that generated this EM field in the first place.

This last formulation suggests that the EM field could be understood as an own entity, such as a particle in Newtonian physics. Given some initial conditions, we can compute the dynamics of the EM field based on Maxwell’s equations. Even more suggestive than this are the conservation theorems we find in EM. The EM field has a density energy and a momentum given by the Poynting vector; the full contributions of the energy/momentum of the particles and EM field of a system are conserved, but not separately. This form of energy propagates through space following a wave equation, such as waves in the water. Its speed is given by the speed of light, which quantifies the speed at which the effect of one electric change can affect another.

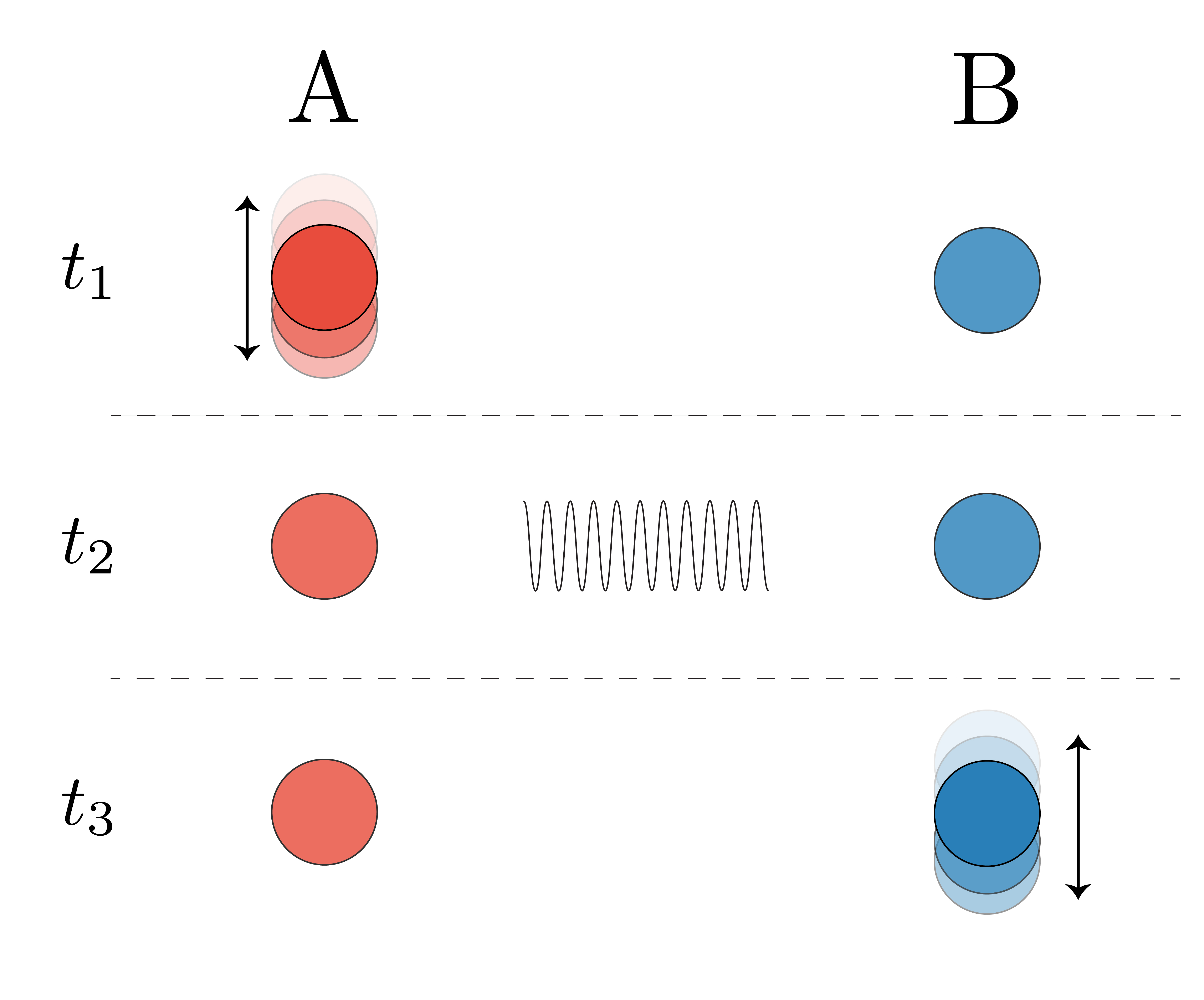

Let’s consider the following example in order to start picturing the main thesis. There are two charged particles, A and B, separated by some distance between them. While B is still, we move particle A a little bit and then we stop the perturbation (time 1 in the figure). Since the speed of light is finite, we need to wait some time until B can feel the effect of moving particle A. During this gap, both A and B are still and an EM wave is traveling from A to B. With some delay, particle B will feel the previous movement of A and will start moving. We can compute this movement by using the Lorentz force. This sequence is illustrated in the following figure

If we freeze the state of the universe at time \(t_2\), the total kinetic and potential energy of both A and B is less that the one at time \(t_1\) or \(t_3\), where there was a positive contribution to the kinetic energy given by the movement of A and B, respectively. During \(t_2\), the contribution of the kinetic energy is zero, which violates the conservation of energy of the particles. Of course, in order to have a full description of the energy of the system we need to include the energy of the EM field. From this simple analysis we conclude that denying the metaphysical content of the electromagnetic field leads us to a violation of the conservation of energy.

Is there anything even more dramatic than discarding the principle of conservation of energy? Well, I think there is. If we want to believe that the EM field has no physical existence and meaning besides just being a simplification of the calculations, we face a more serious problem. Just with the information of the state of all particles at time \(t_2\), we cannot predict the evolution of the system in the future. Effectively, the information about the anterior movement of particle A is not included in the instant physical description of the universe at time \(t_2\). Point in favor for the existence of the EM field.

If you don’t want to believe in the metaphysical content of the EM field or in particles of light, that is perfectly fine in classical physics. Every time someone tells you an electromagnetic wave hits that electron, you can react with well, I would rather say that the electron just felt the remote effect of another charged particle in the universe right now. What you call electromagnetic field is no more than a mathematical construction that you create in order to store all the information about the past in the present. Here, we identify an even more central axiom in modern physics: the notion that if we know everything about the state of the universe right now, we can predict all its future behaviour. I will refer to this as the present hypothesis. This is, in my opinion, an even more important principle than the conservation of energy and it is highly implicit in our modern understanding of nature.

From this analysis, my conclusion is that it is scientific to deny the existence of the electromagnetic field in EM. Following Hilbert’s formalism, we can believe that E and B are just mathematical tools that allow us to manipulate and predict the state of particles in the universe, entities that we create in order to keep track of the past. Accepting this view will force us to drop both the conservation of energy and the present principle. On the other hand, accepting the existence of the EM field helps us to keep two of the milestones in modern science, which of course, are priors of the theory and don’t need validation, they are more like axioms.

Before finishing, I would like to make a few remarks. I think from the moment we start studying physics, the present hypothesis is something we all become familiar with. In Newtonian physics, we learn to solve the trajectory of a particle from its initial position and initial speed. The mathematical setup in EM, fluid dynamics, quantum mechanics, cosmology, and other disciplines is built upon differential equations. In order to solve a differential equation, we need to also provide initial conditions. For random processes, the present hypothesis coincides with the Markov or memoryless property.